[ soundtrack : ‘Your Dog’ — Bob Hund ]

***

This post is too long for email — open in browser for full length.

***

Christmas is creeping ever closer and I’m a busy, little wood-elf beavering away in my underground lair; everything must be finished well in time for Christmas! But not so busy that I can’t pick up a package from Santa’s Canadian workshop. All the way from the ginormous country that seems to be in many ways quite similar to little Norway; home to genial folk like Mattias Wandel, Uncle Bumblefuck (aka AvE) and my favourite tool manufacturers; Veritas. Too bad you Canadians aren’t on the receiving end of the Gulf Stream — it makes all the difference!

The DX60 is a fairly large block plane compared to it’s brethren of similar construction:

Whereas you grip the smaller planes with your fingers, the larger DX60 fits quite nicely in your hand, giving a stronger grip and better ability to apply force and thus remove material. Not as much as a proper, two-handed block plane, but still …

As usual, I buy an extra iron:

The build quality, fit & finish is as always with Veritas: excellent.

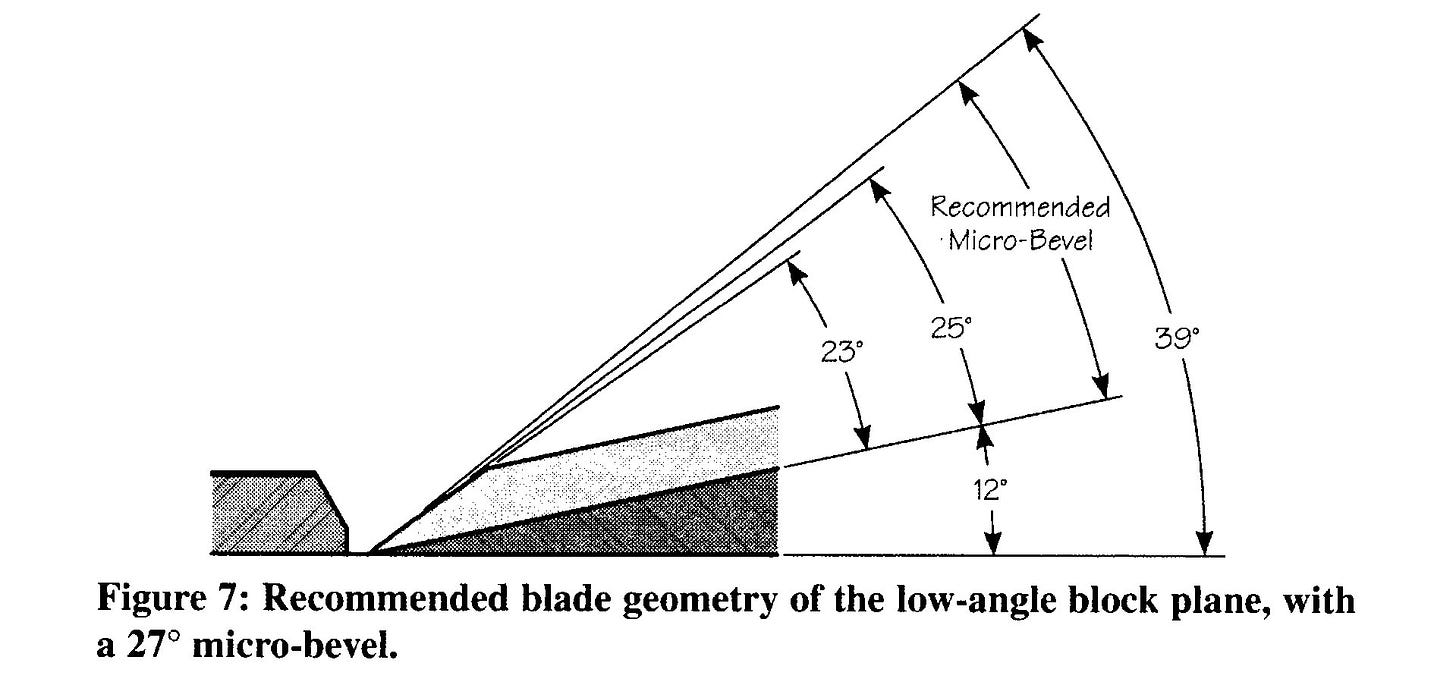

The iron is bedded at 12° and controlled by the usual Norris-style adjuster:

The reason I’ve bought two plane irons is that I intend to use the plane both as a block plane (planing end-grain) and for chamfering and various ‘small-planing’ (planing long grain). Different grain orientation = different cutting geometry. I do not subscribe to the recent American fad of regarding bevel-up, low-angle planes as ‘universal planes’. This is a misconception that one needs a bit of insight into planes and cutting geometry to understand why is wrong (… or at least simplistic). I will not get into that here, but trust me: Planing end-grain or long-grain are two fundamentally different woodworking situations. Yes, you can get a bevel-up, low-angle plane to perform adequately on long-grain — but only as long as you take thin shavings and the grain is not too difficult. There is also a question of relief angles and wear-bevels … it’s complicated — but very interesting! Enough food for a Masters dissertation …

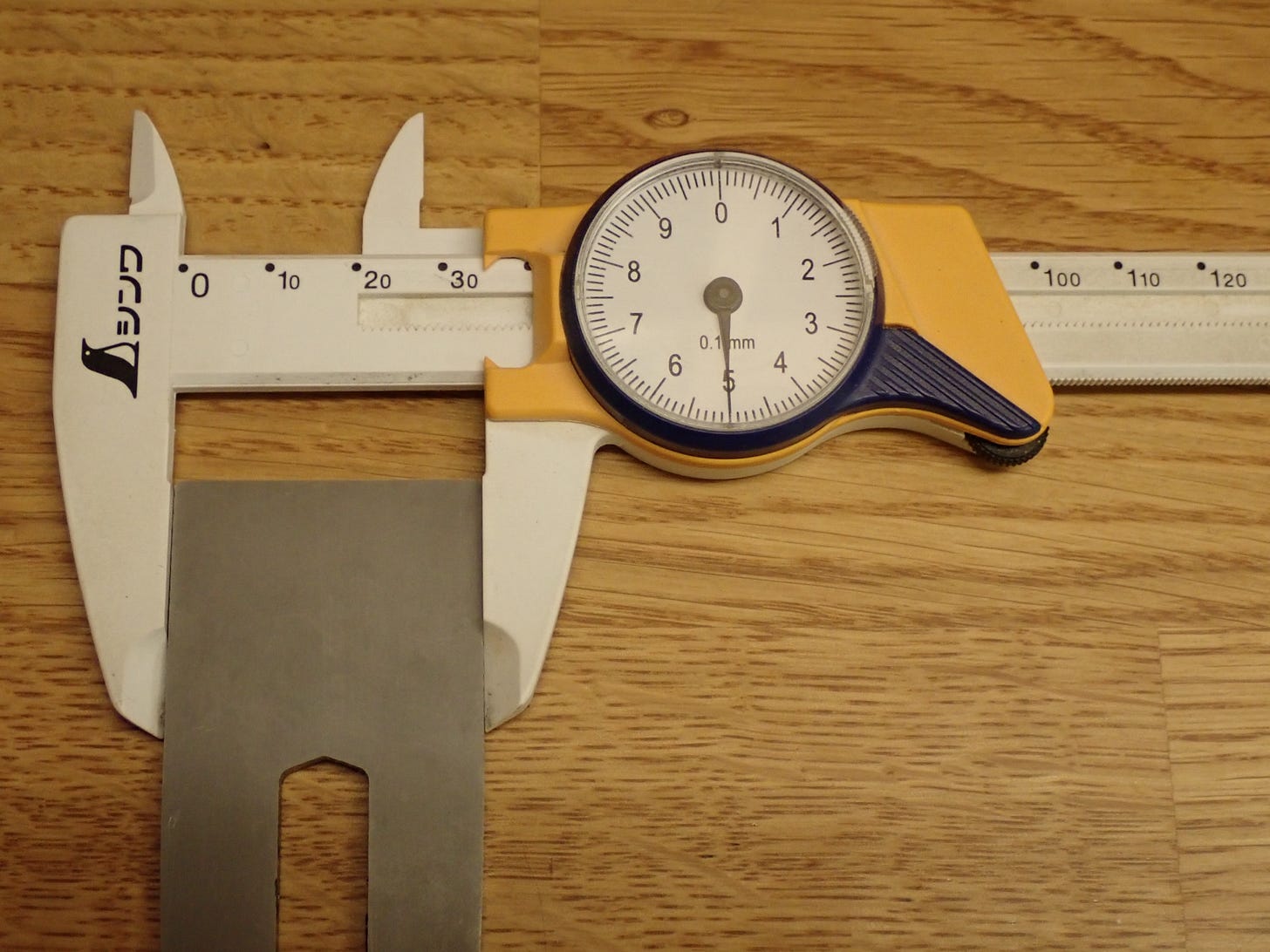

Width of plane iron is a surprisingly metric 35 mm — whatever happened to the fractions of barleycorns?

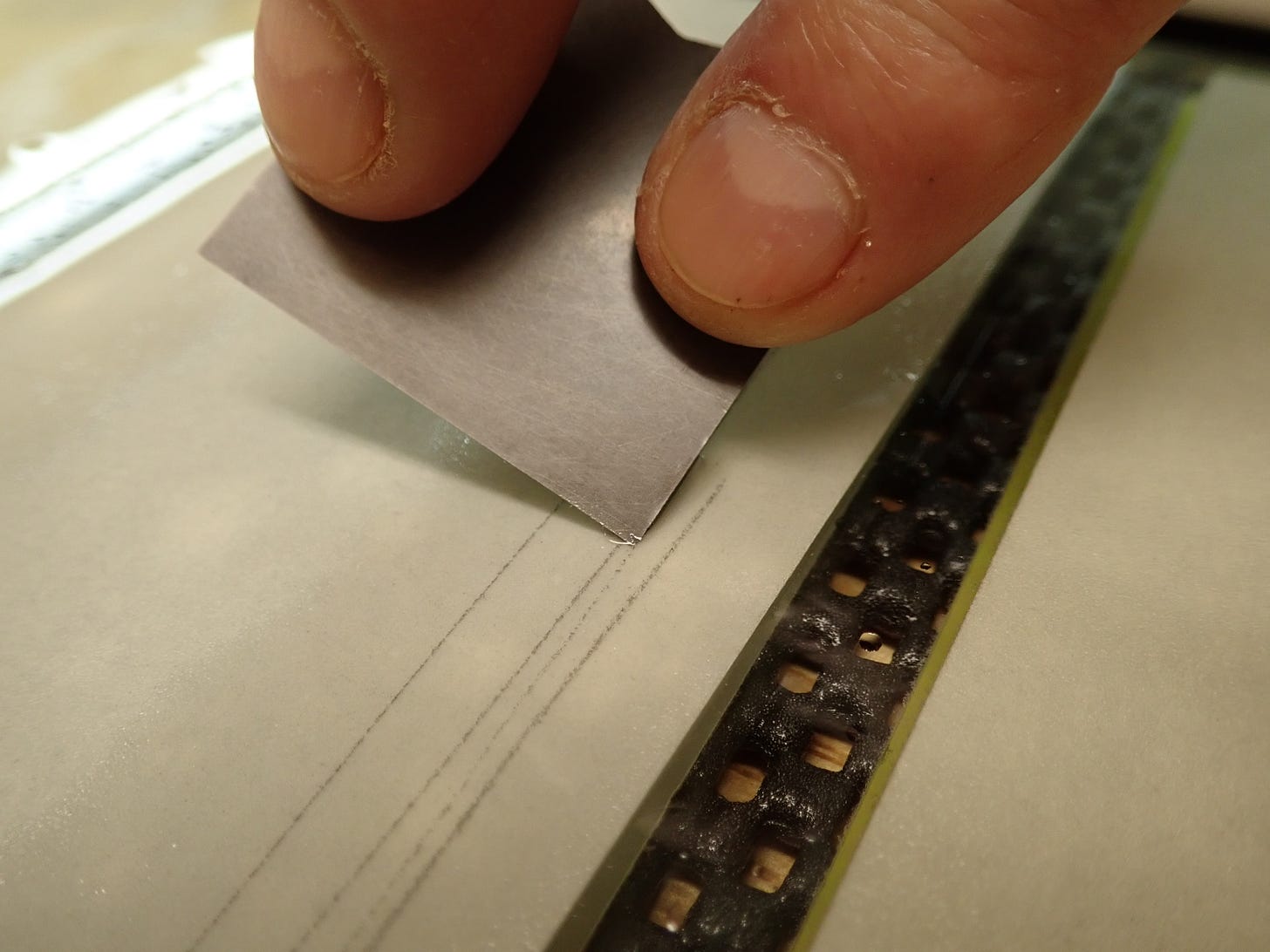

These irons will be honed straight over (with no camber), so the first order of operations is to round over the corners:

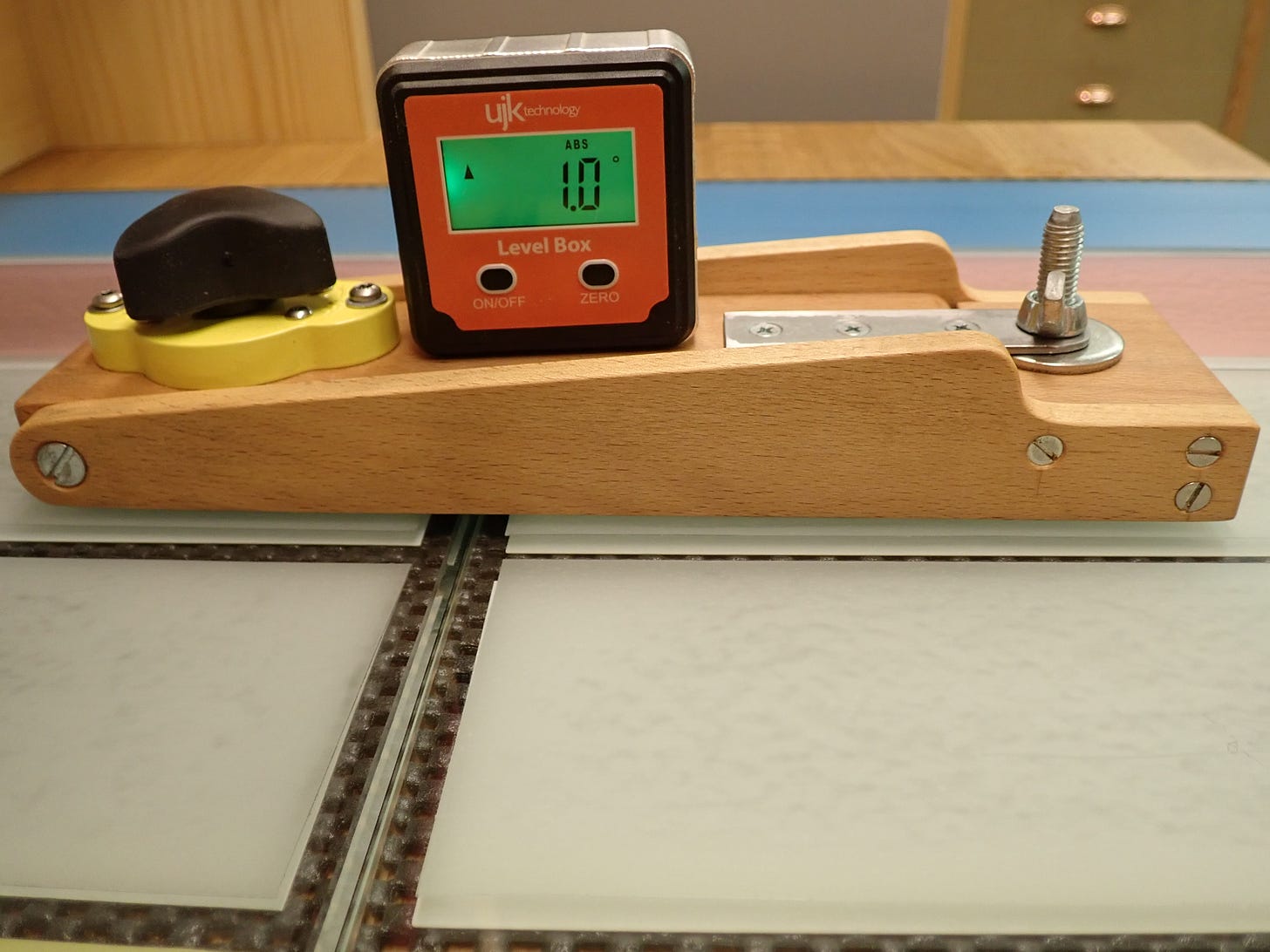

Then a 1° back-bevel using my Magnetic Charlesworth Contraptions:

Yielding a relief angle of 11°.

As for the ‘front’, ‘bevel’ or ‘upside’ of the iron it leaves the factory precisely ground as so:

For my end-grain use I will hone one iron with a tertiary bevel of 27,5° — giving a cutting angle of ca. 40° …

… and for long-grain use the other with a bevel of 35°, giving a cutting angle of 47°.

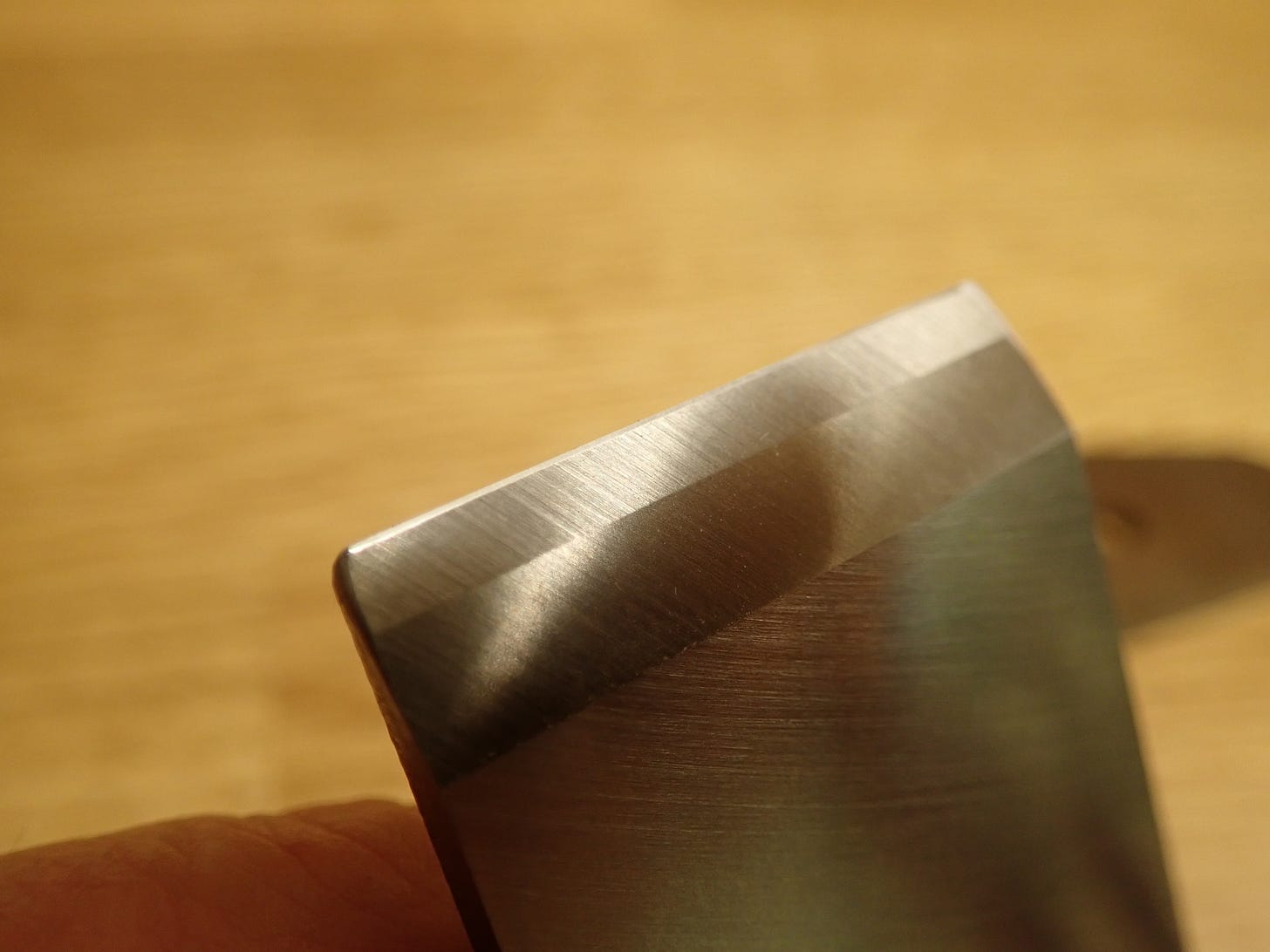

The honed, cutting edge does not have to be wide to do its job. On the contrary; the narrower the honed edge, the less work involved in producing it.

This is a good picture: It shows a plane iron (blade) with it’s three distinct bevels. Being able to hone a specific angle (using a honing guide) greatly increases the quality of the cutting edge and reduces the effort needed to get to ‘wicked sharp’. How do you test if the edge is sharp? I touch it cautiously with my fingertips. If the steel seems to want to cut me, if it feels intent on blood .. well, then it’s sharp.

Do yourself a favour and don’t listen to the reductionists who would have you believe that you might as well hone your edge tools on the curbstone with no adverse effects. This talk reminds me of architects extolling the virtues of raw concrete out of a sense of inadequacy: They know full well that they are ineffectual, effete esthetes — their unmanliness driven home each time they ‘inspect’ a building site. Their misunderstanding being that ugliness, or coarseness equals manliness.

So … how did the new plane perform? Well enough, but it’s waaay to early to tell how it’s best used — it takes time and usage to really get to know a plane and its capabilities. I tried it on some end-grain …

… and it did well, fitting nicely in my hand. Then I tried it on some friendly long-grain:

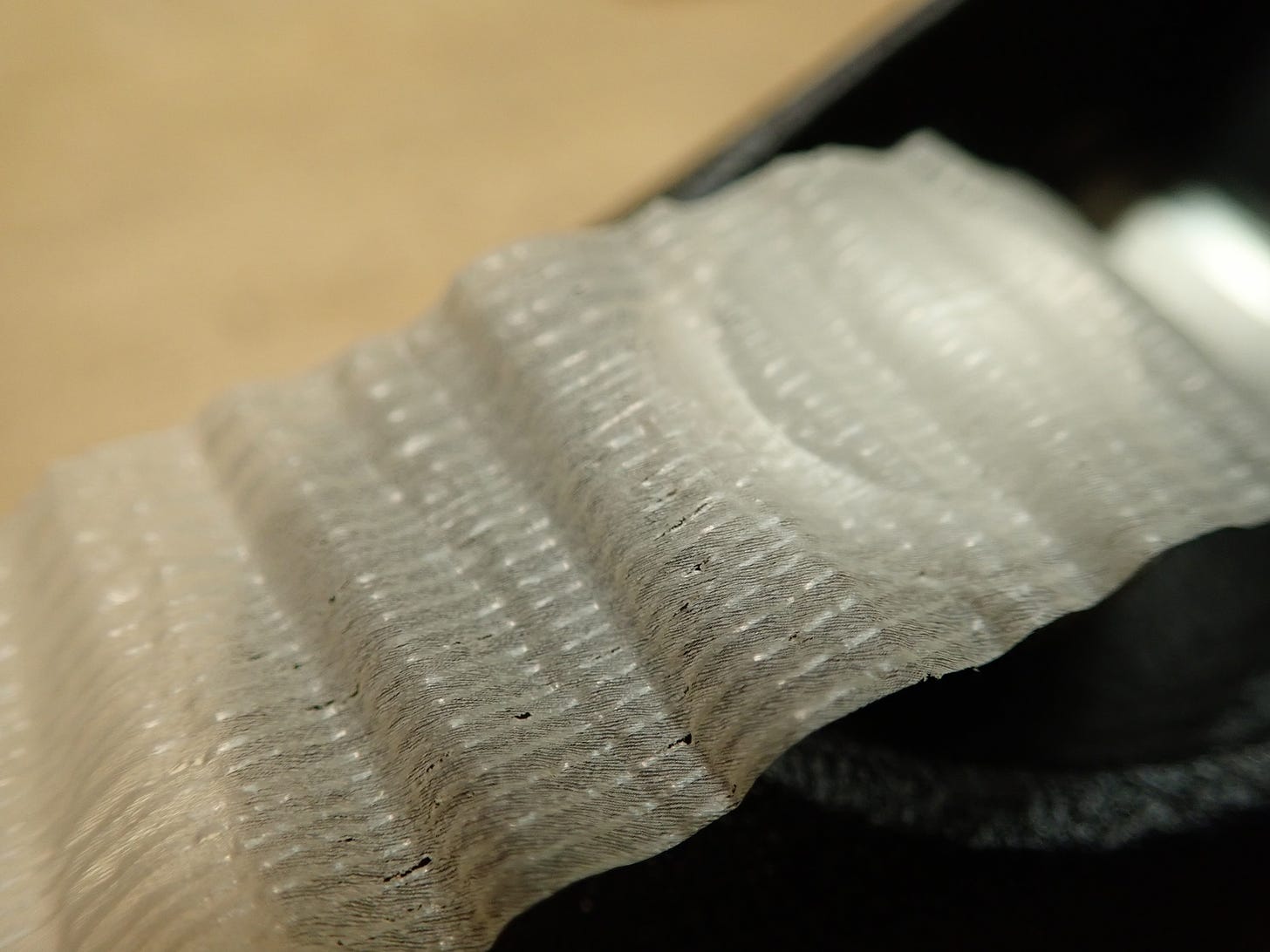

The point — in practical woodworking terms — is not how thin a shaving you may take, but how easily a plane is able to take a thin shaving is a measure of it’s quality. Taking a translucent shaving with ease is indicative of a high quality plane. In practical woodworking terms, you take as few shavings as possible, to save work (number of passes).

Besides, a nice shaving is very informative of the piece of wood you’re working with.

***

During these last 30 years, nothing has given me as consistent pleasure as taking nice shavings off of wood with a hand plane. Yes, I realize how limited that sounds.

I do love a good plane.

***

As _consistent_ pleasures go, this doesn’t sound limiting at all! In fact, it sounds somewhat liberating.