[ soundtrack : ‘Assedic’ - Les Escrocs - POMPLAMOOSE ]

***

A month or so ago I posted a couple of scribblings about chisels — paring and carpenter’s — that seemed to go down well. Since I’ve been a bit summer-lazy lately, I thought I’d fob you off with a reheated post about mallets from the archive.

Mallet and chisels: chips fly and woodworker whistles.

***

A couple of years ago I had some bits of beech left over and some time to waste, so I decided to make some joiner’s mallets. I’d never used this kind of striking tool before, being indoctrinated into believing that only a round carver’s / cabinetmaker’s mallet could rattle the bee’s knees.

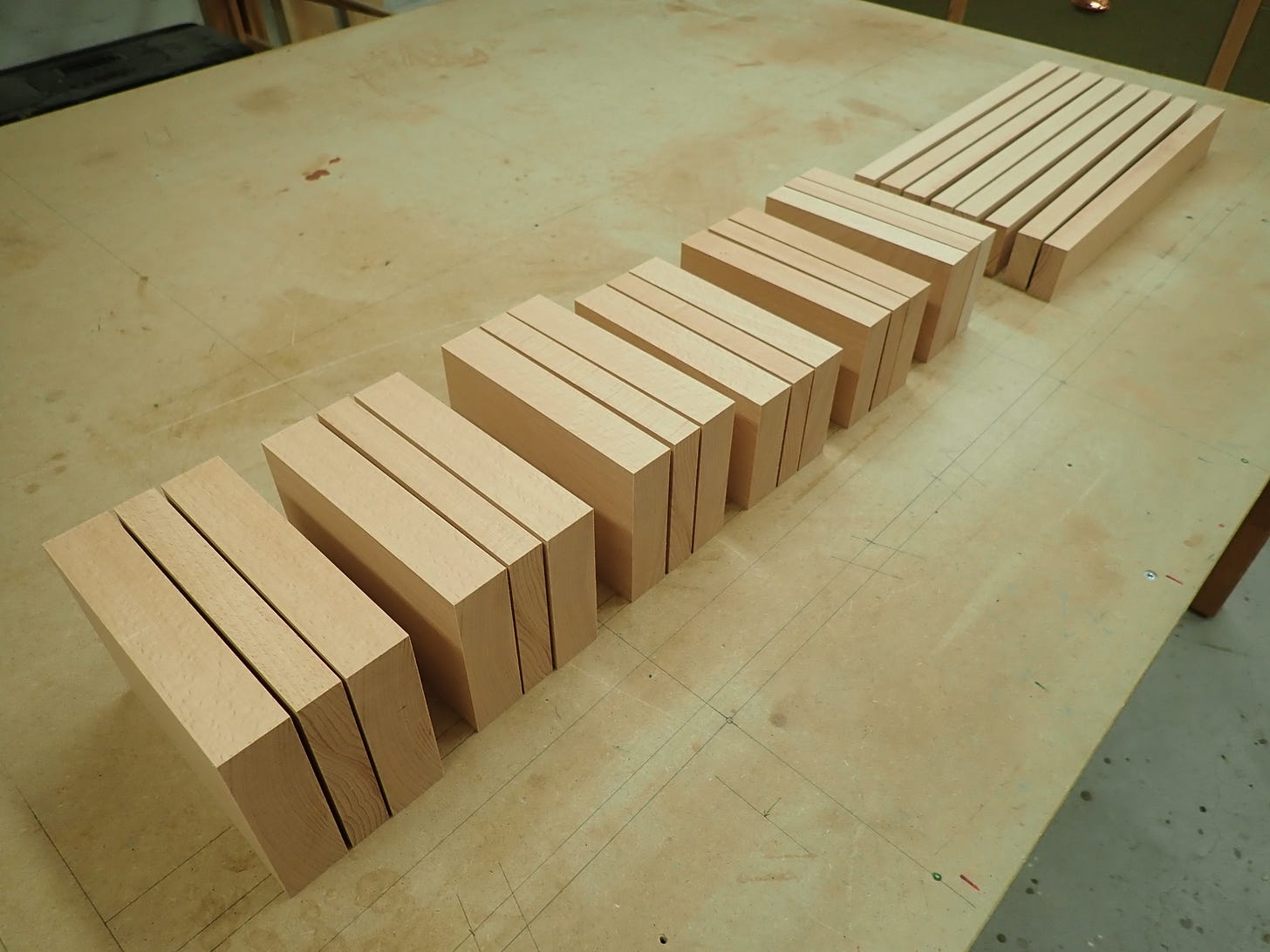

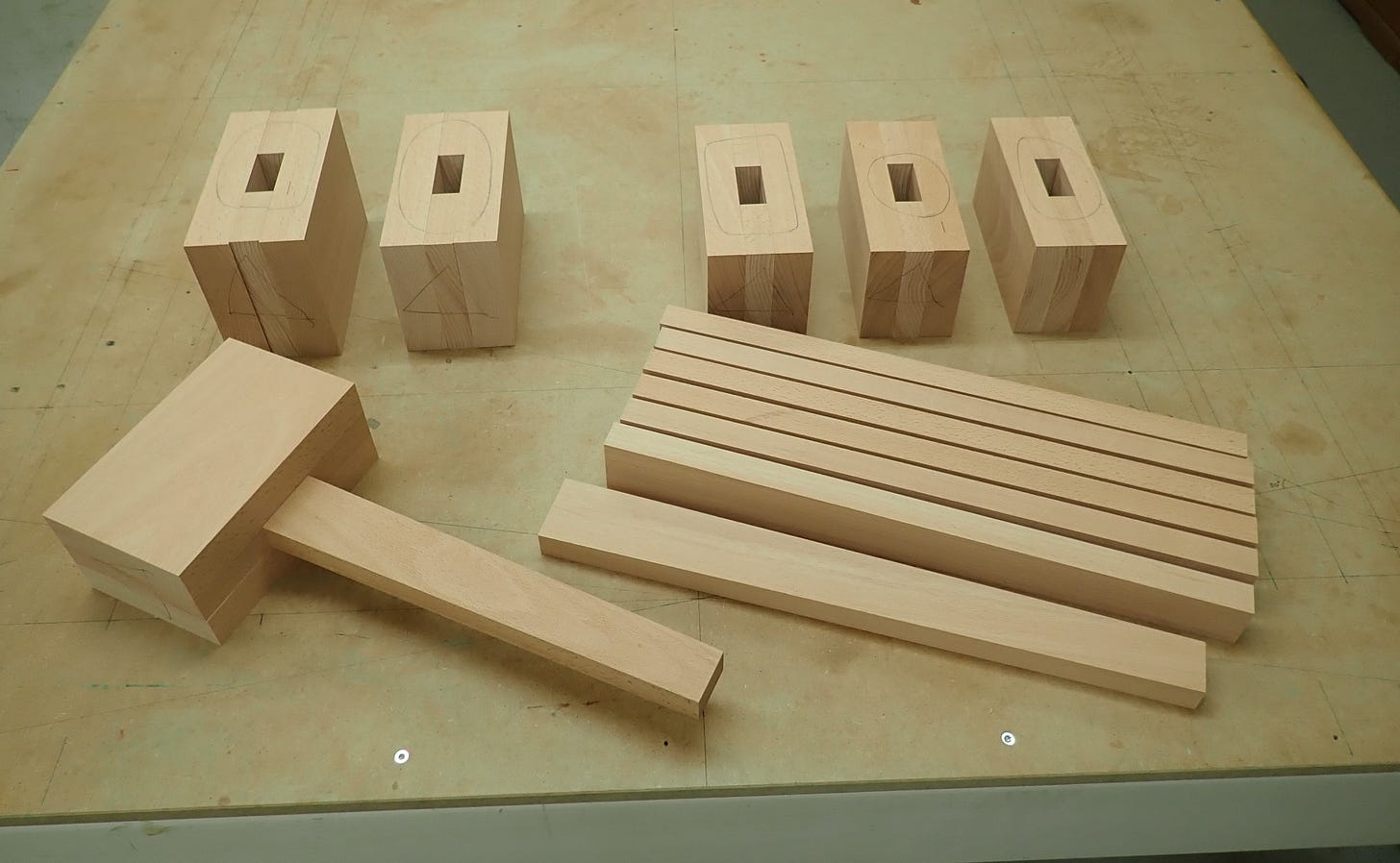

I set out searching the interwebz for info and ain’t they just full of brash, young ‘personalities’ eager to tell you just how to do it (in their strangely dust-free and photogenic workshops). I made notes of all tangible information: measurements, angles etc. and zeroed in on the more credible sources. Synthesizing the various inputs into some ballpark figures on the back of my hand, I cut blanks for a range of sizes to test out which might suit me best.

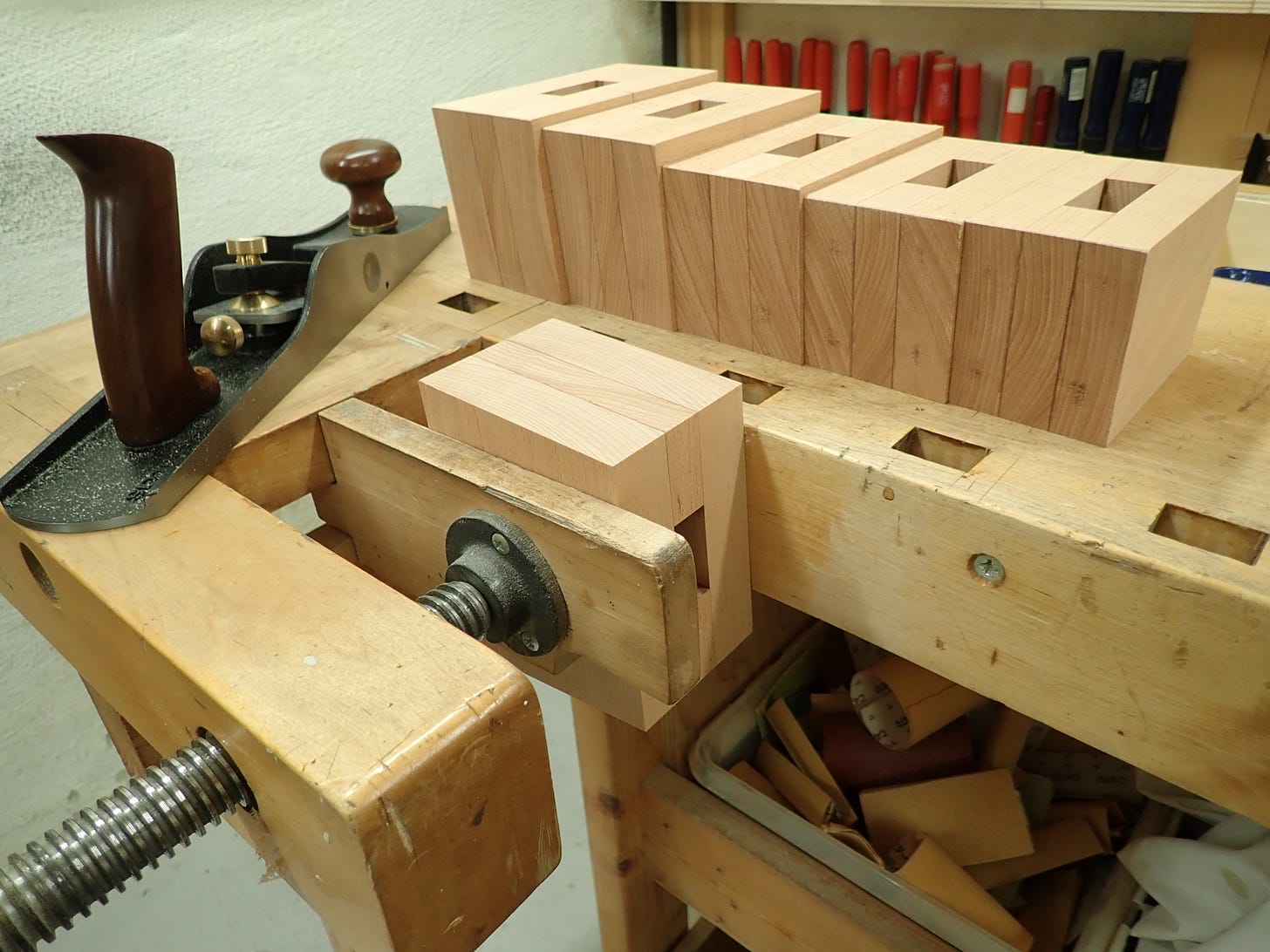

I went for laminated heads and tapering fit handles of varying lengths. The laminations are reinforced with beech dowels and glued with epoxy.

This gave me varying head-weights (& -sizes) with interchangeable handle lengths, offering interesting permutations: light head & long handle? heavy head & stumpy stick? Hey! Don’t you judge me! Life is as interesting as you make it, and ever since my stamp collection was stolen, things haven’t … nevermind.

When ‘wood-finished’ (i.e. ready for surface treatment) I saturated the striking surfaces with diluted epoxy (solvent: acetone) — thirsty wood, beech! — for stability and increased hardness, before soaking all parts for three days in a bath of baby oil / vaseline oil diluted with white spirit — weighted down with flat stones. The idea behind this was that because beech is a dense, and thus dimensionally unstable wood (there’s a correlation there), perhaps I could mitigate that by saturating the wood-cells with mineral spirits, leaving them impenetrable to moisture. I submerged some 1” scraps together with the mallet parts, and when I cut them open after three days, they were fully soaked through (darkened) by the mineral oil.

So … How did I like them ?

Not at all, to be honest. I might have misjudged some vital aspect of the design of these tools, there might be some thing I got wrong … but in my hands, these are not good striking tools — at least not compared to the round mallets I’m used to.

If I were to clothe my objections in words they would be:

1) like a poor tennis racquet, these mallets have a small ‘sweet spot’. When you don’t hit this spot (most of the time!) you have to use muscles in your striking hand / wrist to control the ‘veering forces’. This is tiring!

2) There is no bounce to it! A chisel-striking tool should behave like the opposite of a dead-blow hammer. It should deliver its force in a short, sharp snapp! to give a fast, and thus clean cutting action.

3) The ergonomics are poor — although this might be my fault. These joiner’s mallets need to be actively gripped and struck, by moving your forearm, as when using a steel hammer, unlike my round carver’s mallets that I lazily ‘keep in my hand’ between my three strong fingers and move by clamping down my two weak fingers and snapping my wrist. I’m not a lumberjack chopping down a tree with all my might, I’m more like a woodpecker. Tappety-tap-tap! It is literally all in the wrist.

Perhaps those professions, the wood carvers and the cabinet makers, who spend the most time delicately driving chisles and gouges through wood, have developed a superior understanding of what a good mallet should look like, compared to their coarser brothers the carpenters, who only occasionally need to chop fairly imprecise holes in wood?

I have found limited uses for my joiner’s mallets: I use the smallest one to drive dowels through the cutting plate, and I gave the biggest one to the timber-framing Master to use as a small maul for driving trunnels. It’s a crude tool.

***