[soundtrack : Bre Sarica - Klezmerata Fiorentina - Tales of the Hidden Zaddik]

***

Not much gives me such pleasure as taking delivery of a small load of lumber, sorting through it, deciding which boards to use for the job at hand (that pays for the materials) and storing the rest in my racks and stacks. Lumber in storage represents future possibilities, and wood only mellows and grows more harmoniously relaxed as the years pass. It slowly improves, like good wine in a cellar. It’s like having money in the bank.

By nature, wood is of variable quality, variable size and variable usefulness. Wood is a wonderfully idiosyncratic material, and almost as difficult to assess as human beings. There are few hard and fast rules; you’ll have to trust your intuition, cautiously earned by experience — most of it bitter. Therefore, buying wood can be very difficult, so you always order/buy more wood than you need. The customer, who is footing the bill, ought to have ‘first dibs’ on the choice wood for the job — as decided by you on his behalf, and only within reason! There are some boards/planks that are too good for the work at hand; You might find an exquisitely straight- and edge-grained board, or a beautifully wavy-grained plank of maple or birch in among the usual humdrum consignment. These standouts should be saved for a more deserving project.

The job at hand requires certain qualities from your wood. This means; good enough, but not better! Only a wastrel fool would build a dog-house out of mahogany.

This little woodworking substack has readers on every continent (sounds rather grand when put like that, eh?) and I imagine how wood is bought and sold varies quite a bit depending on where you are on the globe. Lumber is sold at huge warehouses, in small lumberyards and from down the far end of a forest track. I can only write about how things are done in my neck of the woods, and I don’t even know what some things are called in English — that also varies. Bear with me!

Buying lumber can be a daunting task at first. I remember (yes, I’ve reached that age) when I first ‘rocked up’ to the downtown lumber merchant two blocks down from the old trade school, in my almost spotless dungarees, wanting to buy some pine for a little job on the side, and asking for ‘knot-free pine’, me being a discerning furniture maker an’ all ... The guy with the measuring stick just tilted his head and quietly asked “… and what should the small birds sit on while singing?“

To begin with the basics: We mostly use fir and spruce for construction grade lumber. It is sold either at the building-supply warehouse (heard about the dyslexic pimp who bought a warehouse?) where your average civilian can just turn up and spend money (“I need a plank for my bathroom”), or at the tradesmen’s outlet where you need to be a registered company to do business, but where you might get both discounts and credit if they like the sound of your face. And just as important; You don’t have to stand waiting in line behind the hobbyist who needs some bit of plank for his bathroom.

House-building fir/spruce sold as construction grade lumber should be dried to below 18% MC and be graded and stamped according to your regional building code. Building houses can be good money and great fun if you work with a good crew or a mate with a sense of humour, but the lumber-qualities used are not of much interest for finer woodworking; most house-building lumber is fast-grown, knotty stuff. That said; When you’re building a house, you go through a lot of materials, and if you keep your eyes peeled you’ll be able to put aside a few choice boards/planks that are just too nice to waste on construction. And what’s more: If you find an evenly slow-grown piece of fir, and cut free the clear lengths between the knots … there is a lightweight strength in its springy softness, and a quiet beauty in the sheen of its wood. They used it for masts and yards on sailing ships, and wing spars in aeroplanes.

House-building / dimensional lumber is priced by length — or ‘running metres’ as we call it here. The length of each piece is usually stamped on the endgrain, if not tacked on to a label to be digitally scanned. No one misses the 6 metre long measuring stick and the notebook and pencil stub — so slow, tedious and cold in wintertime.

So far, I’ve been talking about buying smaller amounts of wood; the amounts you would transport and shift yourself, on a roof rack, on a trailer or sticking out the back of your truck. If you’re building a house or running a larger workshop, your lumber will likely be delivered in larger packages lifted by crane and/or forklift. Many lumber-merchants collaborate with hauliers that use smallish lorries with ‘palfinger’ cranes mounted behind their cabs, so that they can lift & shift lumber packages into very tight spaces. Over the years I’ve taken delivery of materials at the most unlikely addresses, and been consistently impressed by the driver’s ability to back in and out of the most impossible spots to deliver the timber exactly where you want it. These guys have a spatial awareness second to none. Kudos!

Here in metric-land — which covers most of globe, albeit with some notable exceptions — these larger ‘packets’ of lumber are sometimes measured in cubic metres. Now … intellectually, I’m perfectly able to envision a cubic metre. In my mind’s eye I can effortlessly see a cube of freshwater magically hovering in mid-air, measuring exactly one metre in all three dimensions and weighing exactly one metric ton, but when it comes to lumber … wood … my livelihood … it all becomes somewhat of a three-titted beauty — it’s just too much.

I’ll trust you to notice with which finesse I approach this most delicate of subjects in the woodworking world?

The crux of it: I buy and reckon ‘workshop lumber’ (hardwoods and pine) in inches and feet - because the numbers are easily suitable for quick, mental arithmetic (and because it’s what we’ve always done) - but I design and build in milli/centi/metres - because the decimal method of numerical notation is clearly superior in its simplicity. This little bit of mental flexibility yields the best of both worlds :-)

I’ve gathered that our American friends measure wood by the board foot: an imaginary piece of wood one foot wide, one foot long and one inch thick. It’s a very intuitive unit of measure, especially when buying one inch stock.

My local purveyor of kiln-dried deliciousness uses cubic metres when selling trailer-loads to the industry, but cubic feet when catering to the small-time workshops. Frankly, I’m just grateful for still being able to turn up and buy “Two planks of walnut, please!“ I wonder how long that privilege will last?

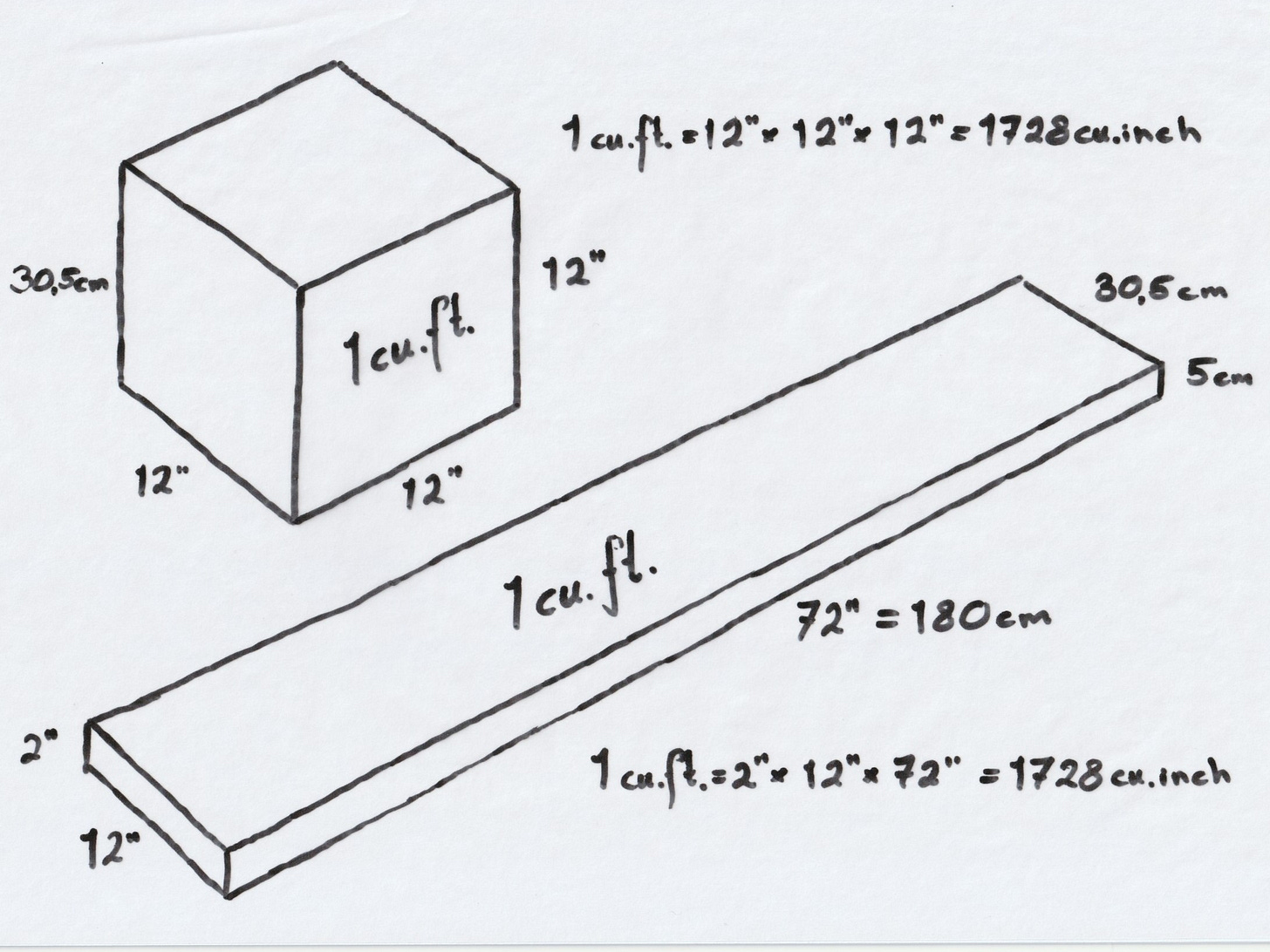

I find the cubic foot to be a very human-sized, and therefore intuitive unit of measurement: a 2-thumb plank, a good foot wide, will make up a cubic foot if it’s roughly a man’s height in length.

1728 is the number to remember.

***

My limited experience of buying wood in the UK has been weird so far. The width and thickness is in inches and the length in meters. The nominal size in mm is given for the width and thickness is provided in mm in brackets.

2" x 2" (47 x 50) x 2.4m for example... As an engineer where only millimetres are used up to something like 3 meters and centimeters are not a real measurement it's been hard to adjust.

I don't yet know how it's going to work out for me in woodworking, most of my tools have imperial and metric scale.

For my shed build the outside dimensions are in feet because for whatever reason when talking sheds it means more to me. But undoubtedly when measuring for pieces that fit inside those dimensions I'll default to millimetres...

I have to work in cubic metres in the woodland. I can take five cubic metres in any 12 week period without requiring a felling license. Trees to cubic metres. Odd. I wonder why we did the cubic thing? Was there a period in time where people glued everything into cubes for shipping? Was this the cubist period?